How the unrelenting growth of NFTs has shifted the art machine into a new cultural moment.

There’s a scene in Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s that sums up how non-fungible token art, aka NFT, is currently being perceived en masse. Midway through the novella, Capote’s protagonist, Holly Golightly, introduces her upstairs neighbour, Jack, to her talent agent, O.J. The two men converse and try to decipher the undecipherable — their mutual acquaintance, the elusive Ms. Golightly. Her agent poses the question — “Is she or isn’t she?”— meaning Is she real or is she a phony? The conclusion on her authenticity does not come without complexity. The men unconvincingly and exhaustively decide that Golightly is both. She’s real and she’s a phony. She’s a real phony.

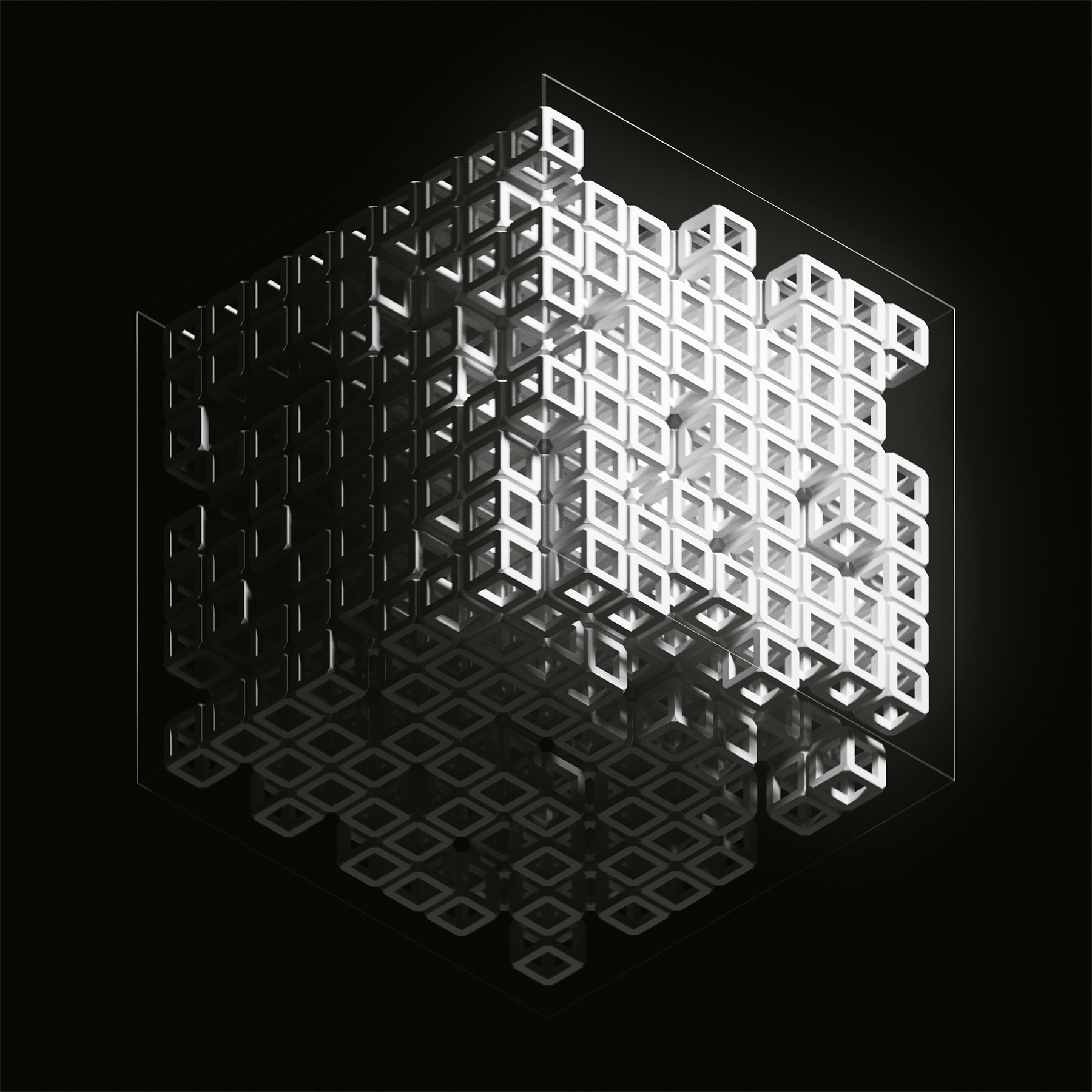

NFT artworks are, for the most part, real pieces of art, but their reputation precedes them — they cannot be displayed at home. NFTs are images, but not physical paintings or photographs showcased on canvas or in frames. Rather, they are digital creations bought and sold, not at a gallery but on a blockchain domain, which is used as an information vessel and a payment address for digital wallets.

The art world is often a place where authenticity is debated. It is, by existence, a world unto itself, a cultural congregate that creates its own universe and language out of the practice of smoke and mirrors. Simulation, replication and reinvention of life — communicated via both curator and creator — is par for the course in any exhibit, yet nothing in the past few decades has confounded the mainstream media like NFT art has.

According to Forbes, NFT artworks are easy to define. “They are like physical collector’s items, only digital…. [I]nstead of getting an actual oil painting to hang on the wall, the buyer gets a digital file.” Time magazine offers another distinction. Think of NFTs as “computer files combined with proof of ownership and authenticity.”

However simple both definitions seem, there are rules to what collectors own and when they own the NFT artwork. For example, NFTs can have only one exclusive owner during a certain time frame, and the data connected to the NFT verifies ownership. This data acts as transfer tokens between the creator and the owner (both of them can store specific information inside the artwork itself). A physical signature on an NFT art piece isn’t an option, and so, it is replaced with an icon or an alphanumeric code within that NFT’s metadata.

So, where does one find NFTs? They’re on blockchains and website domains which are, by the minute, getting better at curating artwork beyond canvas and physical installation. For digital artists such as Shaylin Wallace, who is based in Wilmington, Del., and a recent BFA graduate from Salisbury University in Maryland, these domains have been a lifeline to an art career that couldn’t be dreamed up, let alone developed, five years ago.

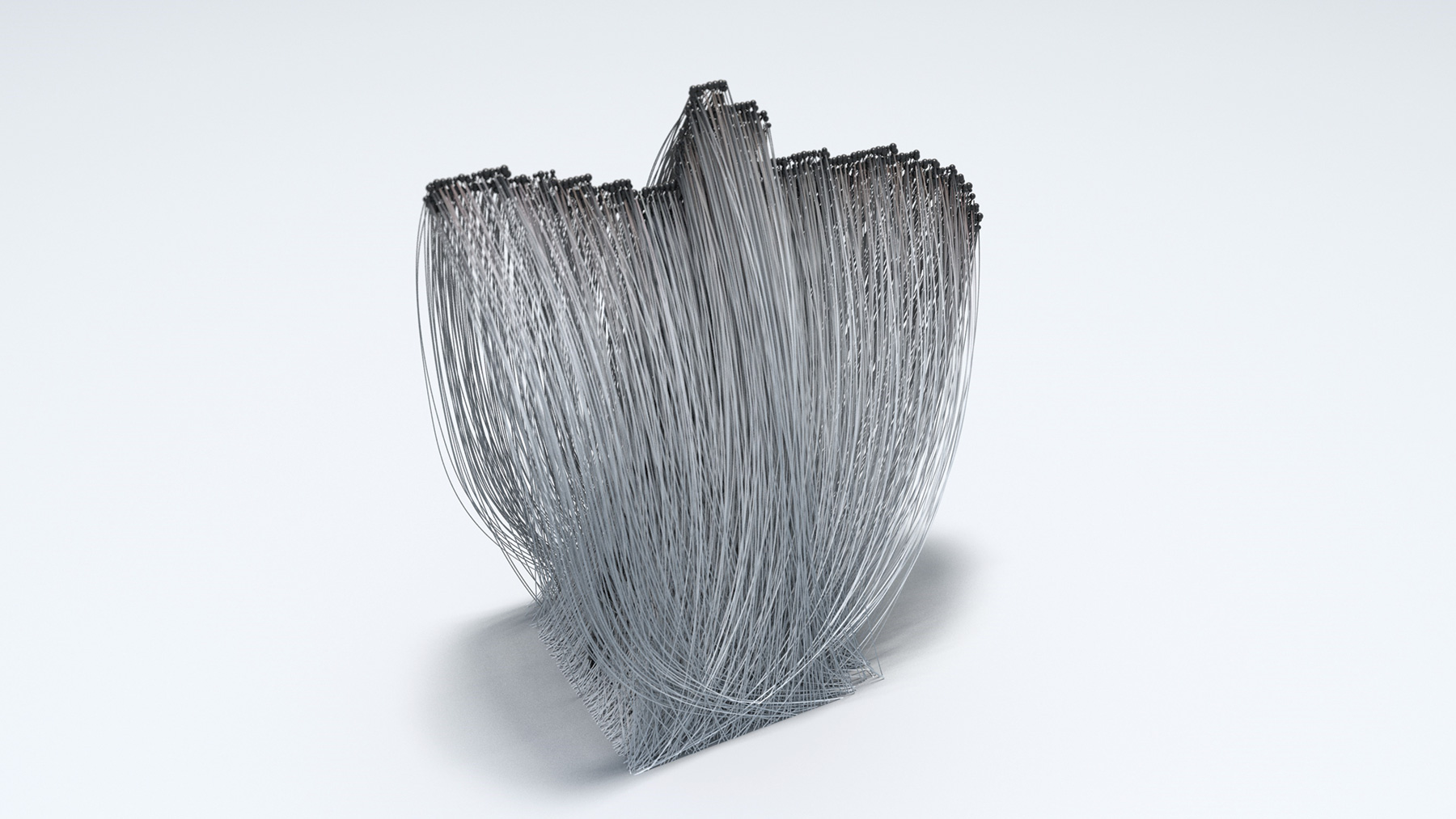

“You could say blockchains are like digital galleries, these tiny centres of freedom because they offer these great opportunities for artists like me to basically get paid our worth,” Wallace explains. “The fact is, it is difficult to be a digital artist and get compensated and acknowledged properly. Painters can sell their original paintings and get paid a good amount, but [for me] as a visual digital artist with assets on my computer rather than in a physical form, that value is harder to identify and NFT sites and blockchains are making it easier.” Wallace believes there is little difference between what she sees as a paintbrush and canvas and, say, her mediums of choice, which are graphic design applications, such as Photoshop. “I’m not the only one thinking this way,” she notes. “The rise of NFTs has proven that the way we think about art is changing fast.”

How fast? Well, according to a recent report by ArtTactic, a leading market analysis firm with more than two decades of experience surveying the global art industry, there has been a 511-percent increase in online-only sales over the course of 2020. This epic spike in sales and interest has motivated a new generation of art collectors, makers and digital native-art professionals to continue breaking new ground and become globally recognized without the aid of a gallery or international press. A prime example is a record-breaking event this past April, when Sotheby’s sold approximately US$17 million worth of NFT artwork at its first-ever crypto sale and auction of works by the digital artist Pak.

This radical transformation in the art world is a welcome one for Wallace. “My work isn’t owned by one single gallery. I have the right to sell and exhibit various pieces in different parts of the world on blockchain sites. This whole new wave of art is giving power back to artists who wouldn’t necessarily have the chance for visibility,” she says, noting too that unlike at a traditional gallery, she dictates when and where her work is viewed.

“As a Black female artist, I can definitely say from experience that most major galleries have favoured white male artists. NFTs take you out of that old world system,” Wallace continues. She explains that many BIPOC and LGBTQ+ artists have been instrumental in pushing the envelope. “Many artists on the fringe or who are disenfranchised or ignored, those who would never have gotten a chance for their work to be recognized, have now become leaders in a way that has never happened before.”

The very idea of curation — that is, the way artists are being presented and promoted — is also getting a makeover of sorts.

A fledgling Vancouver-based company, Ethos Multiverse Inc., has deemed itself “a creator-first NFT platform” that allows artists to build their own digital universes.

Founded by a half-dozen art investors — including Todd Towers, Ethos’s director and a long-time art consultant, and Matias Marquez, a fintech (financial technology) expert — this platform is currently working with both emerging and established NFT artists to help them cast a wider net and connect them with potential art buyers who are still figuring out how NFT art works.

“The new collector, like the creator, is starting to write the rules against the old guard. They don’t necessarily need an XYZ gallery to tell them what to see. Artists also can dictate the terms of self-sovereignty in this way,” Towers points out.

“Our goal is to make the exchange extremely simple for the right side of the adoption curve,” says Marquez, referencing Ethos’s mission. “People like my mom and my aunt, those who have never held cryptocurrency ever before, need to have a place to go to easily purchase and trust that they are interacting in a safe way.” This summer, Ethos assisted Winnipeg-born artist Bradley Harms in creating a sold-out bidding war for his Triple Fold (2021), wherein a single edition of said piece was “dropped” once a day for 10 days. Well versed in how collectors’ behaviours have changed through the years, Towers views art collections as portable vaults that allow collectors to sell pieces like playing cards..

“I can walk around Art Basel with my phone and have my wallet with NFT digital collectibles on [it],” says Towers. “And when I meet [other collectors], while I’m having a glass of wine, they can see that I’ve acquired a limited-edition work and I’d be able to sell it to them on the spot.”

The next step in the evolution of NFT art is figuring out a way to conquer what has been unconquerable in the past — the ever-powerful lure of the art fair. Art Basel, Frieze, Scope and NADA (New Art Dealers Alliance) have proven to be the events where next-level shifts in the art market take place.

This year, Parisian gallerist Stéphane Lebenson is launching Deep, a brand-new AI-focused art fair scheduled to hit London, October 13–17, and then head over to the San José Museum of Art in Silicon Valley in 2022. Deep was born to “present experimental and pioneering NFT art in ways it has yet to be showcased,” notes Lebenson. “In other words, we are looking at merging that physical experience with a digital [one], so that external feeling and internal [feeling] can be experienced.”

Lawrence Weiner, Jack Elwes and the French art collective known as Obvious are just a few of the announced headliners in the lineup of talent Lebenson has culled for the Deep event.

“The artists here are disruptors,” says Lebenson. “They are unapologetic futurists who often get their own authenticity questioned, but they don’t care. They realize NFT art and AI art is like a new world colliding with a dinosaur. NFT art is punk rock, and the traditional art system is a dusty classical ballet. All we want to do is show people that there is more out there [beyond] the ballet.”

Elio Iannacci – *This article originally appeared in INSIGHT: The Art of Living | Fall 2021.