Film has a way of capturing life in a way that cannot be captured through other forms of art, yet at the same time it encapsulates all forms of art.” So says Caroline “Coco” Monnet, an artist, activist, theorist and institution-builder whose love for and devotion to film has made her a regular presence at film festivals — including Cannes — along with leading contemporary arts institutions around the world such as Paris’ über-modern Palais de Tokyo and the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal(MAC) closer to home.

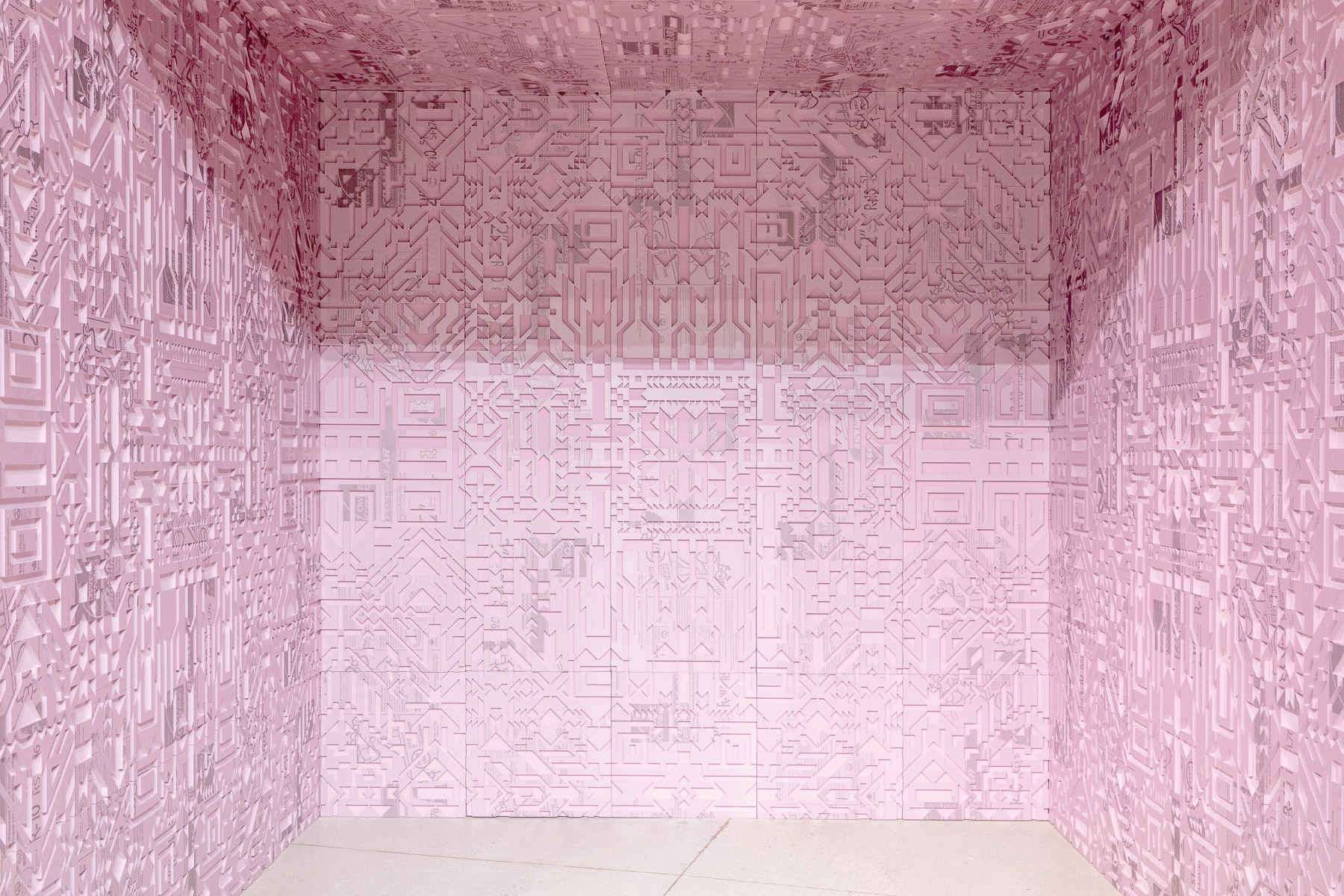

Still in her 30s, yet with a CV that seemingly scrolls without end, Monnet uses film to both express her colour-rich, vaguely geometric, organically-inspired aesthetic while giving voice to the native Anishinaabe culture she has increasingly championed and identified with throughout her eclectic career. “Everything that I do is embedded with my identity, my values and philosophy of the world around me,” Monnet says. “Each of the works I create resists the colonial hold that our current society has on Indigenous people, in particular women.”

Mostly self-taught, Monnet comes from a home filled with respect for art, creativity and, most crucially, curiosity. Born in Ottawa and raised between Quebec’s Algonquin territory of Outaouais and the coast of Brittany in France, Monnet — whose sister is noted playwright Emilie Monnet — describes her parents as “avid consumers of music and film, although they were not artists at all.” Nonetheless, considering the success of the sisters, art and culture clearly shone throughout her childhood. “My mother’s curiosity was contagious,” she said, “and I believe curiosity has to be one of an artist’s main personality traits.”

Her journey to art started after completing degrees in communications and sociology from the University of Ottawa and a brief spell studying at the University of Granada in Spain. Her oeuvre is nothing if not expansive, straddling painting, sculpture, installation pieces and, of course, cinema. “I want people to feel an emotion and live a sensory experience when they visit my work,” says Monnet who has been inspired by both Canadian and global artists such as Alanis Obomsawin, Nadia Myre, Teressa Margolles, Akira Kurosawa and Olafur Eliasson. “Maybe that is why my practice is so interdisciplinary.

Take “Hydro”, a particularly striking work from 2019 realized in collaboration with Ludovic Boney. The piece is essentially a light sculpture – in both the most far-reaching and literal and truest forms. At once a piece of collectible design and an interactive, mixed-media display, the piece features some 180 light bulbs hanging close to the ground on sturdy wires assembled like an intricately illuminated geometric chandelier.

Each bulb’s intensity rises and recedes in tandem with an accompanying soundtrack anchored in a 1992 speech delivered by Matthew Coon Come, Grand Chief of the Cree nation delivered in support of Indigenous rights. The piece is equal parts art and social- justice statement — all the while feeling effortlessly compelling and beautiful.

Or consider the highly-celebrated short film Tshiuetin, which made an appearance at TIFF and was nominated for a Canadian Screen Award. The French-language short takes its name from Tshiuetin Rail Transportation, an Eastern Canada rail concern whose Labrador to Schefferville, Quebec line came under First Nation control in 2005. The documentary explores this unique ownership structure, which was the first of its kind in Canada.

No matter the specific work, “all of my projects have been a learning curve both professionally and personally. And each new project is a new challenge,” Monnet says. “I love the research aspect of my practice where I need to find solutions as I figure out the most effective ways to tell a story,” she says.

Despite her broad artistic purview, Monnet says she is hardly finished with expanding her oeuvre. Up next is a solo exhibition at the influential Arsenal Contemporary Gallery in New York, along with a new feature film she is currently writing with support from the Sundance Institute through the Merata Mita fellowship, named after the notable Maori filmmaker — support that specifically supports Indigenous female feature-film directors. Monnet has also aligned herself with Virtual Reality and is designing a VR experience to be produced with the National Film Board of Canada.

Still, Monnet — whose distinctive cinema work has landed her in enviable positions at both the Cannes and the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) — says she still harbours one great ambition: “I would love to direct a contemporary opera one day,” she says.

Like so many young artists, Monnet straddles a wide range of worlds — artist, filmmaker, woman, Indigenous, European and Canadian. She understands, and also resists, the tendency for folks like herself to be assigned labels and put into boxes. “I’m an Indigenous artist, but I am also French. I live in Quebec, but it tends to want a different identity than the rest of Canada”

As for the larger Canadian scene, Monet says Canada still becomes lost within the North American narrative that remains US-centric. Nonetheless, it’s the pairing of Indigenous culture within the Canadian creative scene that Monnet finds most exciting right now. “I can say without a doubt that some of the most avant-garde and groundbreaking work and ideas are coming from the Indigenous arts community,” she says. “It’s original, grounded in tradition, rooted in the community and hopeful for the future.”

By David Kaufman – *This article originally appeared in Insight: The Art Of Living Magazine – The Passion Issue.