“May you live in interesting times” is an old saying-cum-“curse” that’s wide open to interpretation. “Interesting times,” however, pretty much sums up the situation in today’s world — environmental change, geopolitical unrest, real-estate bubbles. It would also be interesting to look back in time and see how change has affected culture, specifically the art world.

Up until the emergence of independent galleries and dealers in the 19th century, in Western art, patrons commissioned work directly from artists. And those patrons generally represented the estates — i.e., the church and the nobility — which a critic would most like to challenge.

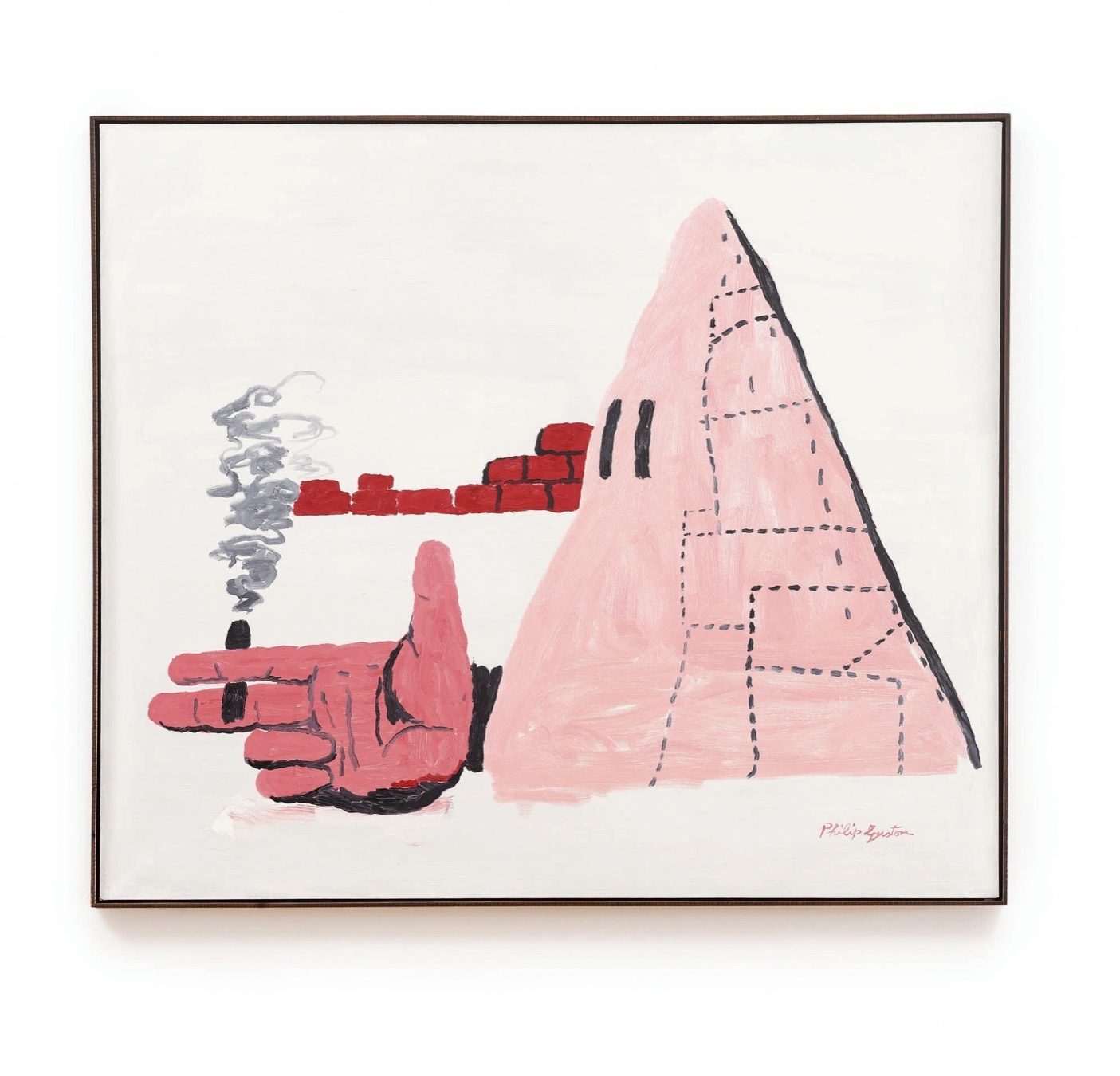

The Spanish painter Francisco Goya, who made overtly political etchings while painting portraits of courtiers, was probably the first to use his medium for his own message, paving the way for “statement work” to seep its way into the subsequent centuries.

In fact, our 21st-century mayhem seems quite stable compared to the 20th century, which was full of unrest — two world wars and one long cold war, the Spanish Flu and other pandemics, segregation, apartheid, famine, two great depressions and unheard-of prosperity, plus social and technological upheaval.

There are many other ways art influences the culture at large — not just those with lots of disposable income and, often, not in the way the artists intended. In the gilded age of the late 19th century, industrialists donated their private art collections to the public to make themselves seem less opportunistic.

It should also be noted that Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump, currently in the sights of the U.S. media, have used art to boost their brands. Trump’s Instagram feed often displays works by emerging artists such as Nate Lowman, Dan Colen and Alex Da Corte. Richard Prince, known for his controversial practice of appropriating images, made a portrait of Ivanka based on an Instagram post, sold it to her for $36,000 and then denounced it as “fake art.”

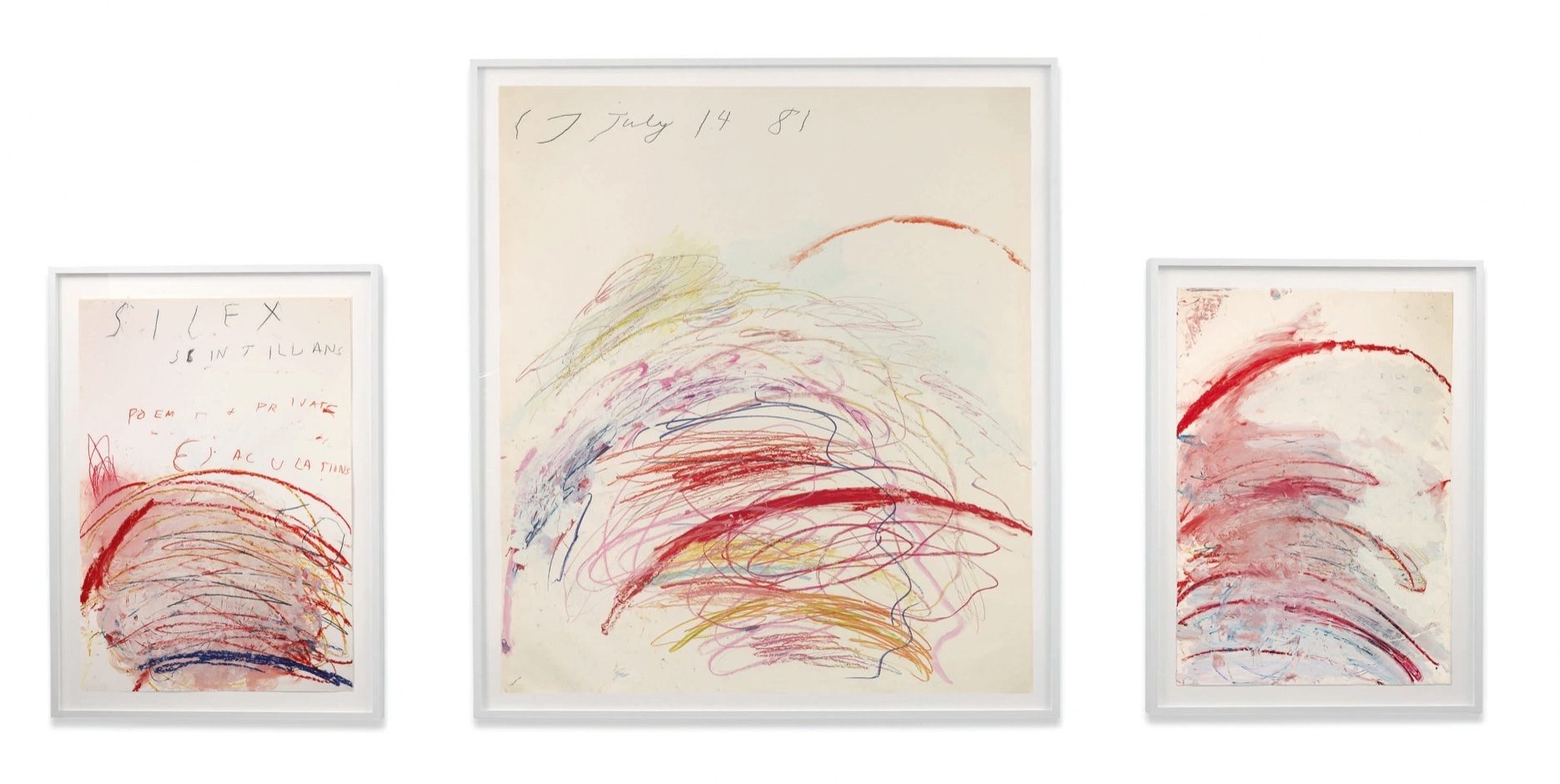

In our modern age, art has also become a hedge against uncertain economic forces. Unlike real estate, art is portable and therefore more liquid when times become unstable.

And unlike stocks, art is tangible; it has value as something to be enjoyed and interacted with every day. Which means that in a topsy-turvy world, we seek solace and affirmation from art.

“If there have been any bumps on the road, all that means is that buyers are looking at ‘safe’ purchases,” says Vaughan. “This is not a great time to be an emerging artist — but there rarely is a good time to be an emerging artist.”

Even established contemporary artists are also having a hard time navigating the current cultural turbulence. It’s not easy to create a message in a post-truth world. At this year’s Venice Biennale, for example, artists tried to address big global themes like the refugee crisis and indigenous culture, while trying to take in what seems to be another new affront every day. As a result, critics called this year’s exhibition “comfortable” and “bland.”

Vaughan notes that, right now, there are “artists that provide welcome distraction or artists who reaffirm the worldviews of the buyer or viewer.”Says Vaughan, “Everyone is so fragile today [that] they are rushing to buy [or] see works that confirm what they already believe to be true. There is no room for questioning art right now. Nobody has the patience.”

The artists who do manage to balance popularity with a personal message are the ones that seem to have the most enduring influence. Pablo Picasso produced a prodigious amount of work, but his masterpiece, Guernica, remains one of the most powerful anti-war messages ever generated. Created in response to the bombing of a Basque village, Picasso’s mural drew immediate worldwide attention to the Spanish Civil War.

Whether making an emotional or a financial investment in art, one must take a long-view approach, even in turbulent times. An artist’s influence can take years, even decades, to reveal its effect.

For example, just as feminism is having a resurgence in response to everything, from wage disparity to controversial remarks made by world leaders, the work of female artists such as Agnes Martin, Georgia O’Keeffe and Bridget Riley are being discovered anew.

Works by artists outside of the traditional Western canon are also gaining attention. Seven years after the death of Kananginak Pootoogook, in 2010, this Inuit artist’s small, intimate pencil drawings were a revelation to audiences in Venice. Pootoogook was instrumental in taking Inuit art out of the anthropological worldview.

In turn, Vancouver-based multimedia artist Geoffrey Farmer, whose work has been influenced by Inuit artists, visited Pootoogook’s home in Cape Dorset, Nunavut, to inform, for the Canadian pavilion at the Biennale, his own piece about intergenerational loss.

In the case of Basquiat, his work was a reflection of New York City as he knew it during the economic stagnation of the 1970s and ’80s. Thirty years before Black Lives Matter and the shooting in Ferguson, Mo., Basquiat painted Defacement (The Death of Michael Stewart), depicting the last moments of a 25-year-old graffiti artist who was beaten by the police in 1983.

Basquiat took street art to galleries and museums and used his art-world street cred to address issues like police brutality.

Today, in a world of social media platforms and personal branding, we call that “reach.” And in a good way.

By Rhonda Riche – *This article originally appeared in INSIGHT: The Art of Living | Fall 2017

Photos: Courtesy of Sotheby’s