Elizabeth Brandeis-Morrison and Craig Morrison have always surrounded themselves with art. From their salad days in San Francisco in the 1990s and through multiple moves that led them from California to Canada, the couple, now Toronto residents, have pulled together an impressive collection of works by contemporary pop artists such as Toronto-based Fiona Smyth and Gary Basemen in L.A., who recently completed a collaboration with rebel-shoe brand Doc Martens.

Along with portraits that Brandeis-Morrison inherited from her family, the couple’s art collection has always played a prominent role in their lives. “It’s more than an investment. Each piece marks a time in our [lives],” notes Morrison, an educator and founder of the high school program Oasis Skateboard Factory, which is geared to at-risk youth in Toronto as a way to earn academic credits by running business enterprises focused on skateboards and street art.

The couple have established lasting relationships with many artists including Smyth and Ness Lee over the years, and most of their drawings and paintings document personal memories and the childhood of Mollie, their now-adult daughter. When Mollie moved out on her own, they sold their large, cozy house and purchased an open-concept loft with soaring ceilings but much less wall space. The couple’s attention shifted from acquiring their next big art purchase to downsizing their collection. They then faced a dilemma. What do you do when you have too much of a good thing?

Moving to a new home or a change in life phase could trigger the decision to pare down possessions, including beloved artworks. First-generation collectors may be looking to divest themselves of some art pieces or may wish to trade up, while second- or third-generation owners inheriting an estate may not have the means or the interest to take on someone else’s passion for art.

Much time, effort and emotion are involved in acquiring artworks, so when the time comes to divest, the collections deserve the same care and attention. There are four options available to those faced with culling their art pieces — sell, give to family and friends, donate to an institution, or storage.

The first step is to catalogue and document the provenance of each painting, drawing and sculpture. Jot down as much information as possible about the artwork — its title, the medium (watercolour versus acrylic paint, for example), its dimensions and the artist’s name. Include a description or a photo, as well any artist’s notes and receipts from galleries.

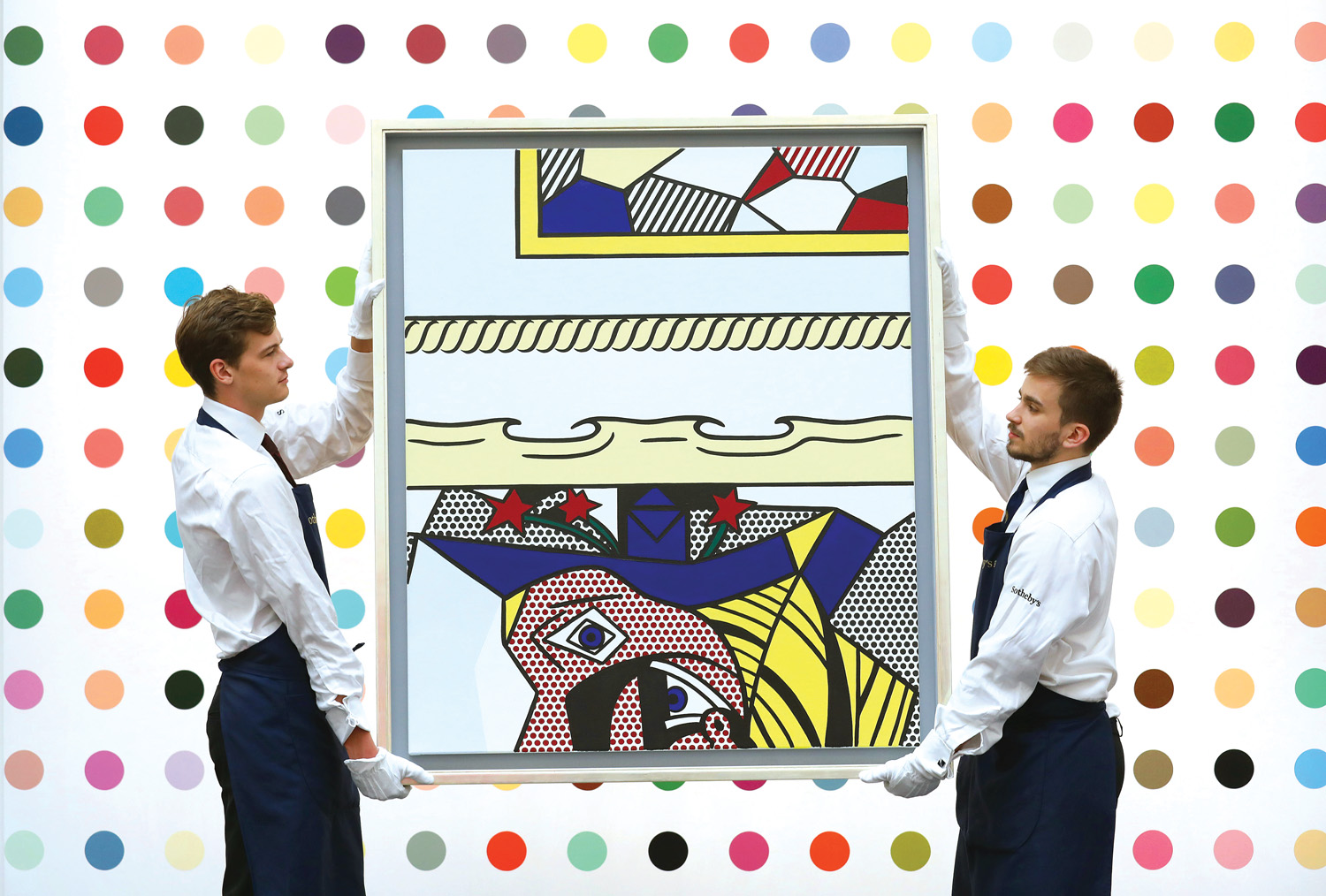

C. Hugh Hildesley, executive vice-president of Sotheby’s, warns collectors to be prepared to face some hard truths when culling their art pieces. First, very few people who seek to sell are able keep their collection together. As an auctioneer, Hildesley has conducted some of Sotheby’s most prestigious sales, including the estate of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, the property of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor and the baseball memorabilia of Barry Halper. For a grouping of artworks to remain intact, the collection must be “exceptionally focused,” says Hildesley, such as the Picasso ceramics of Lord and Lady Attenborough. Or if your collection is more eclectic, like David Bowie’s, it helps to be a “legendary influence,” he notes.

Second, should you choose to sell, it’s best to not go it alone. Consider consulting with a gallery or an auction house, as they are well qualified to match your artworks with purchasers who will be good stewards of your treasures. You’ll also get a better return compared to what you’ll receive if you try to sell the pieces yourself. If you need to divest quickly, an auction is probably your best option. If you want to make more profit and you have time to find the right buyer, a gallery is a safer bet, but there is a downside to consigning art — if it fails to sell, you will earn nothing.

Distributing your collection among friends and family is another popular solution that would also allow you to visit your favourite works. But keep in mind that something you love may not spark joy in other people, so finding the right home for various art pieces could involve a lot of time, effort and, possibly, disappointment.

Donating your archive to an institution, say, a museum or public gallery, is another alternative. In the past, patrons tended to leave gifts to galleries in their last will and testaments, but nowadays, donors frequently opt to bequeath their art collection while they’re still alive and well. In fact, thanks to the modern lifestyle trend to simplify and declutter, a good number of Gen-Xers and baby boomers are downsizing. As a result, many institutions simply don’t have room to accept every artwork or collection, and if they do, the divesting process can be time-consuming.

For example, at the University of Toronto’s Art Museum, the time involved in taking in an art piece or collection can be anywhere from two to six months or even longer. Each artwork must pass the condition examination, curatorial consideration, adjudication of an acquisitions committee, the university’s protocols and stages of acceptance, and the signing of agreements. And even then, your art pieces may end up in storage rather than being on display to the public.

If it’s important to you that the collection be appreciated by a broader audience, consider donating to a hospital, school or charity. The donation may qualify as a charitable deduction on your taxes.

And if you simply can’t part with your art collection, storage is your best option, albeit likely an expensive one. Hildesley points out that personal tastes and the reasons for paring down are constantly changing, and storage gives you time to re-evaluate these factors.

While the secondary market is flooded with 1970s-era artwork, most fine art by listed artists is worth hanging on to. Landscapes are especially popular now, he notes, and you can always rotate stored art with pieces in your home. Just remember that paper, paint and other materials are sensitive to light, temperature and humidity, so pick a storage facility with expertise in handling art.

In the end, collectors Elizabeth Brandeis-Morrison and Craig Morrison decided to break down their artworks into two parts — “the ‘A’ collection, things we couldn’t live without seeing every day; and the ‘B’ collection, pieces that I’ve had forever and couldn’t imagine selling or giving away,” Morrison says. Some artworks went to live with their daughter, family favourites went to the cottage, and a few pieces went to a storage unit.

Now with less art on display in their home, the couple can showcase more important works. “It was an opportunity to not have as much stuff,” he says, “and to be able to appreciate more what we have.”

By Rhonda Riche – *This article originally appeared in INSIGHT: The Art of Living | Spring 2018

Photos: Kate Green/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images ; Sotheby’s ; Philip Toscano/PA Images/Getty Images ; Bettina Strenske/Avalon/Newscom